1.2 Physics simulation

Only a brief summary of ArtiSynth physics simulation is described here. Full details are given in [11] and in the related overview paper.

For purposes of physics simulation, the components of a MechModel are grouped as follows:

- Dynamic components

-

Components, such as a particles and rigid bodies, that contain position and velocity state, as well as mass. All dynamic components are instances of the Java interface DynamicComponent. - Force effectors

-

Components, such as springs or finite elements, that exert forces between dynamic components. All force effectors are instances of the Java interface ForceEffector. - Constrainers

-

Components that enforce constraints between dynamic components. All constrainers are instances of the Java interface Constrainer. - Attachments

-

Attachments between dynamic components. While technically these are constraints, they are implemented using a different approach. All attachment components are instances of DynamicAttachment.

The positions, velocities, and forces associated with all the

dynamic components are denoted by the composite vectors

![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() .

In addition, the composite mass matrix is given by

.

In addition, the composite mass matrix is given by

![]() .

Newton’s second law then gives

.

Newton’s second law then gives

| (1.1) |

where the ![]() accounts for various “fictitious” forces.

accounts for various “fictitious” forces.

Each integration step involves solving for

the velocities ![]() at time step

at time step ![]() given the velocities and forces

at step

given the velocities and forces

at step ![]() . One way to do this is to solve the expression

. One way to do this is to solve the expression

| (1.2) |

for ![]() , where

, where ![]() is the step size and

is the step size and

![]() . Given the updated velocities

. Given the updated velocities ![]() , one can

determine

, one can

determine ![]() from

from

| (1.3) |

where ![]() accounts for situations (like rigid bodies) where

accounts for situations (like rigid bodies) where ![]() , and then solve for the updated positions using

, and then solve for the updated positions using

| (1.4) |

(1.2) and (1.4) together comprise a simple symplectic Euler integrator.

In addition to forces, bilateral and unilateral constraints give rise to

locally linear constraints on ![]() of the form

of the form

| (1.5) |

Bilateral constraints may include rigid body joints, FEM

incompressibility, and point-surface constraints, while unilateral

constraints include contact and joint limits. Constraints give rise

to constraint forces (in the directions ![]() and

and ![]() )

which supplement the forces of (1.1) in order to enforce

the constraint conditions. In addition, for unilateral constraints,

we have a complementarity condition in which

)

which supplement the forces of (1.1) in order to enforce

the constraint conditions. In addition, for unilateral constraints,

we have a complementarity condition in which ![]() implies no

constraint force, and a constraint force implies

implies no

constraint force, and a constraint force implies ![]() . Any

given constraint usually involves only a few dynamic components and so

. Any

given constraint usually involves only a few dynamic components and so

![]() and

and ![]() are generally sparse.

are generally sparse.

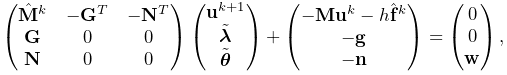

Adding constraints to the velocity solve (1.2) leads to a mixed linear complementarity problem (MLCP) of the form

|

|||

| (1.6) |

where ![]() is a slack variable,

is a slack variable, ![]() and

and ![]() give the force

constraint impulses over the time step, and

give the force

constraint impulses over the time step, and ![]() and

and ![]() are

derivative terms defined by

are

derivative terms defined by

| (1.7) |

to account for time variations in ![]() and

and ![]() .

In addition,

.

In addition,

![]() and

and ![]() are

are ![]() and

and ![]() augmented with stiffness

and damping terms terms to accommodate implicit integration, which

is often required for problems involving deformable bodies.

The actual constraint forces

augmented with stiffness

and damping terms terms to accommodate implicit integration, which

is often required for problems involving deformable bodies.

The actual constraint forces ![]() and

and ![]() can be determined

by dividing the impulses by the time step

can be determined

by dividing the impulses by the time step ![]() :

:

| (1.8) |

We note here that ArtiSynth uses a full coordinate formulation, in which the position of each dynamic body is solved using full, or unconstrained, coordinates, with constraint relationships acting to restrict these coordinates. In contrast, some other simulation systems, including OpenSim [7], use reduced coordinates, in which the system dynamics are formulated using a smaller set of coordinates (such as joint angles) that implicitly take the system’s constraints into account. Each methodology has its own advantages. Reduced formulations yield systems with fewer degrees of freedom and no constraint errors. On the other hand, full coordinates make it easier to combine and connect a wide range of components, including rigid bodies and FEM models.

Attachments between components can be implemented by constraining the velocities of the attached components using special constraints of the form

| (1.9) |

where ![]() and

and ![]() denote the velocities of the attached and

non-attached components. The constraint matrix

denote the velocities of the attached and

non-attached components. The constraint matrix ![]() is

sparse, with a non-zero block entry for each master component to

which the attached component is connected. The simplest case involves

attaching a point

is

sparse, with a non-zero block entry for each master component to

which the attached component is connected. The simplest case involves

attaching a point ![]() to another point

to another point ![]() , with the simple velocity relationship

, with the simple velocity relationship

| (1.10) |

That means that ![]() has a single entry of

has a single entry of ![]() (where

(where ![]() is the

is the ![]() identity matrix) in the

identity matrix) in the ![]() -th block column.

Another common case involves connecting a point

-th block column.

Another common case involves connecting a point ![]() to

a rigid frame

to

a rigid frame ![]() . The velocity relationship for this is

. The velocity relationship for this is

| (1.11) |

where ![]() and

and ![]() are the translational and rotational

velocity of the frame and

are the translational and rotational

velocity of the frame and ![]() is the location of the point relative

to the frame’s origin (as seen in world coordinates). The corresponding

is the location of the point relative

to the frame’s origin (as seen in world coordinates). The corresponding

![]() contains a single

contains a single ![]() block entry of the form

block entry of the form

| (1.12) |

in the ![]() block column, where

block column, where

![[l]\equiv\left(\begin{matrix}0&-l_{z}&l_{y}\\

l_{z}&0&-l_{x}\\

-l_{y}&l_{x}&0\end{matrix}\right)](mi/mi1791.png) |

(1.13) |

is a skew-symmetric cross product matrix.

The attachment constraints ![]() could be added directly to

(1.6), but their special form allows us to

explicitly solve for

could be added directly to

(1.6), but their special form allows us to

explicitly solve for ![]() , and hence reduce the size of

(1.6), by factoring out the attached velocities

before solution.

, and hence reduce the size of

(1.6), by factoring out the attached velocities

before solution.

The MLCP (1.6) corresponds to a single step integrator. However, higher order integrators, such as Newmark methods, usually give rise to MLCPs with an equivalent form. Most ArtiSynth integrators use some variation of (1.6) to determine the system velocity at each time step.

To set up (1.6), the MechModel component

hierarchy is traversed and the methods of the different component

types are queried for the required values. Dynamic components (type

DynamicComponent) provide ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() ; force effectors

(ForceEffector) determine

; force effectors

(ForceEffector) determine ![]() and the stiffness/damping

augmentation used to produce

and the stiffness/damping

augmentation used to produce ![]() ; constrainers (Constrainer) supply

; constrainers (Constrainer) supply ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() , and attachments (DynamicAttachment) provide the information needed to factor out

attached velocities.

, and attachments (DynamicAttachment) provide the information needed to factor out

attached velocities.